To Steppen, 10,000 years ago, energy, or his concept of energy, was a Fire. He could feel and see the forces of nature in the Sun, the wind, and storms that would batter his relatively frail and unprotected body. And he knew the power of water flowing in the rivers that could sweep entire villages away – but he had no way to harness those energies. Fire was his connection to forces beyond his normal personal abilities – and in the case of Fire – he could carry it, or the knowledge to re-create it, with him – anywhere. For Steppen, the concept of more energy, meant simply, more fire.

Most scientific sources point to the control of fire by early humans as a turning point in the cultural aspect of human evolution. Fire allowed humans to cook food, maintain warmth through cool nights, and it offered protection from the predators of the dark (both animal and insect). And whether it was a “carried” burning lump of coal, the potential sparks within a properly struck flint, or from the friction of sticks rubbed together – fire, or the tools to create it, had to be mobile to be of use to the nomadic hunter-gatherers that were our ancestors.

Carbon-dated evidence of the widespread control of fire dates to approximately 125,000 years ago. There is also evidence, and support for the controlled use of fire by Homo erectus even as long as 400,000 years ago – while claims for the earliest evidence of controlled fires range up to 1.7 million years ago. I imagine that Mankind has fallen asleep to, and woken up to, the sound (and smell) of crackling fires for an incredible amount of our history.

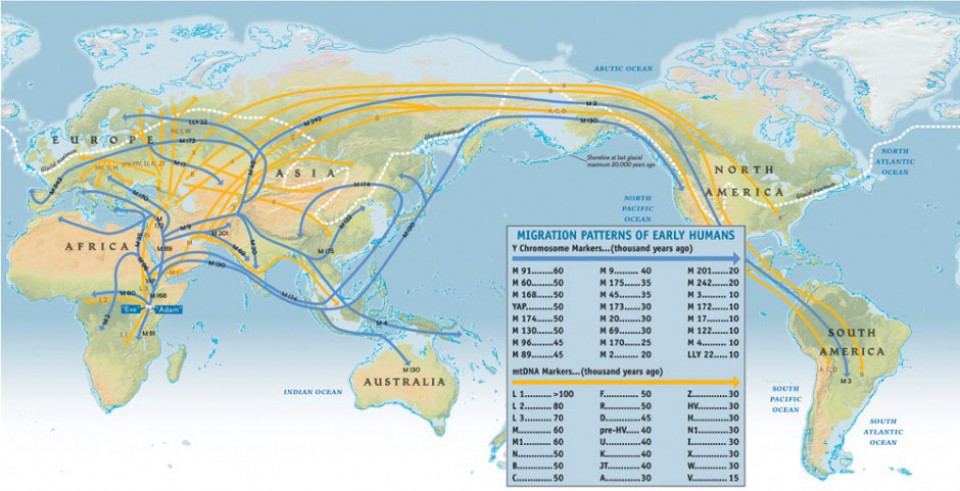

As mankind left the cradle of Africa about sixty thousand years ago and began to populate the lands north of the Mediterranean Sea, the ability to start and maintain fire became even more important. Europe and parts of Asia are capable of severe winters, even at moderate latitudes. And where it might have been a little different in the temperate Central African zones, the spring and fall nights of central Europe can dip into frigid temperatures on a regular basis. NO group could survive long-term there without large fires – throughout the night – almost every night. The Neanderthals had already survived in the area for a few hundred thousand years – if there was communication between the two (and evidence says there was), then knowledge about Fire production, and cold weather survival, must have changed hands.

Wind was also one of the earliest forces of nature to be harnessed by Humans. It filled the sails of the boats that early fishermen plied in the coastal waters of the Mediterranean Sea. There is no indication sails were ever utilized by the Neanderthals, and they still existed up until about twenty thousand years ago. However, the evidence of sails, even woven-reed ones would be hard-pressed to survive the erosive nature of time and water.

At nearly the same time, water was probably beginning to be dammed, and directed for Human uses – but remember, this was probably late in the evolutionary “game” because, as nomads, water was where you found it. You went to it, it did not come to you. It would only be when Humans started to settle down, about eight thousand years ago, that “technological” needs for the control of water arose – the first need was irrigation – diverting water to dry acreage. The second was finding a way to grind-down the larger, and larger volumes of wheat (and other grains) that were being produced. Eventually large water driven grinding wheels served the purpose. About this same time, water was also beginning to be “irrigated” into the new small farming communities for Human use – for consistent drinking water and even sanitation services! (Something the Romans would perfect). Irrigated farms, and their domesticated animals (horses and oxen) brought new, even more personal power sources. Large animals were now trained to be harnessed to help maintain fields.

Somewhere in there, the widespread use of coal, and oils made an appearance. They allowed fire and heat to extend beyond the life of a log, and could even provide you with fire when there were no logs to burn.

So a simple Energy timeline might look something like this:

One million years ago to over a hundred thousand years ago – Fire harnessed.

Eight to Ten thousand years ago – Wind, Water, and Farm Animals controlled.

Only three hundred years ago (1712), the first man-made energy source, Steam, was harnessed for industrial use… Let me say that again, of our millions of years as Humans, only three hundred years ago, we created our first useful, man-made energy source. It still required natural energy (water and fire) to “create” the steam, but the output could be regulated which made it extremely useful.

The ability to build a large enough metal tank, and a release-valve mechanism which could control the pressure, was the key. The pressure could then be released in a manner that could precisely turn gears, cogs and wheels (ultimately even trains!).

And then, it was discovered that steam could turn a turbine fast enough to produce electricity. Thank you Mr. Tesla.

In 1859 the first commercial oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania in the United States. Petroleum gave us truly portable energy we could carry in a can. The gas burning engine followed suit, and we put them, and gas, in all of our machinery that moved – cars, airplanes, boats, chain saws, etc… It’s interesting that, even though gasoline isn’t really used to heat us directly, as in NOT in our houses, in a very short period of time it has become the number-one choice of Human use of energy worldwide. Our government will allow oil companies to drill in your back yard if it thinks it can find more. We have billions of little fires going on all the time – in almost every moving piece of equipment you can name. Sadly, where there’s fire there’s smoke.

It has been a whirlwind of innovation since then. And in all cases of energy production, up until about sixty years ago, more energy always meant MORE fire, steam, water, whatever… All just in the last few hundred years.

It has become obvious that we all can’t have our own campfire. We can’t have 8 billion personal fires going all night long around the world – that could consume over 8 billion trees a week, not to mention the smoke! And it’s obvious that solar, wind, geothermal, and water technologies,while improving all the time, are limited to certain geological locations.

The question is whether or not can we create safe, efficient, and LARGE enough power sources to provide energy for 8 billion humans?

***

Well, there was the atom-bomb, followed by atomic energy – less that seventy five years ago. The military was all over it, and its first useful technological application was as a heat source to produce steam to propel Navy submarines. Part of the thought was that the uranium being used could be easily kept cool with the constant supply of cold sea-water, and another was that in a submarine, containment of the fission material was maximized and safe at sea if there was ever a mishap.

Atomic energy, it seems, was not necessarily a case of “more” being better, it became a case of very careful control of the small amounts you had. That is a real change.

But, since we all agree that it is still pretty volatile technology, even seventy five years later, it does make many people still wonder about its future prospects.

In light of this, the United States has decided to pursue nuclear fusion, and is directing its huge amount of research dollars in that direction. It would seem that we like our energy to be volatile, just in case we need to make more weapons.

So what else is out there? Are there any other elements that contain the potential for energy – without the threat of blowing us up, or contaminating the air and sea water (like those reactors in Japan after the tsunamis, or leaking oil tankers)?

Certainly many people are looking, and a few think they may have an answer: Some are thinking about Thorium.

The Periodic Table of Elements is a grouping of the known elements in our universe, assembled in order of their atomic weight. The light gases are first like Hydrogen (#1) and Helium (#2), and there are non-metals like Silicon (#14) and Sulfur (#16), and at the end, there metals like Gold (#79), Lead (#82), Radium (#88), Thorium (#90), and Uranium (#92).

The elements at this end of the chart are called the “heavy” elements, and they are at the end of the range of metals that can remain stable under normal earth atmosphere conditions. All of the elements on the periodic table numbered after them (above #92) are pretty much man-made – created in a lab – they are just too unstable to naturally exist in nature. Uranium is the last one and the whole world is aware of its rarity, and the technology required to harness it.

First, what about #91, Protactinium? Well, the average concentrations of protactinium in the Earth’s crust is typically on the order of a few parts per trillion. Because of its scarcity, high radioactivity and high toxicity, there are currently no uses for protactinium outside of scientific research, and for this purpose, protactinium is mostly extracted from spent nuclear fuel.

So now, back to #90, Thorium.

It seems to be safe, plentiful, and non-hazardous. Here is this from Encyclopedia Britannica at www.Britannica.com:

Thorium (Th) is a dense silvery metal that is softer than steel. It has a high melting temperature of approximately 1,750 °C (3,180 °F)… Finely divided thorium metal will burn in air, but the massive metal is stable in air at ordinary temperatures (although it will react with oxygen to form a surface tarnish after prolonged exposure). Because of its reactivity, it is extracted from minerals only with difficulty.

Almost all thorium found in nature is the isotope thorium-232 (several other isotopes exist in trace amounts or can be produced synthetically). This slightly radioactive material is not fissile itself, but it can be transformed in a nuclear reactor to the fissile uranium-233. Since thorium is present in the Earth’s crust in about three times the quantity of uranium, its fertile quality represents a virtually unlimited source of nuclear energy. In order for this theoretical value to be realized, however, the barriers of costly extraction and conversion techniques would have to be overcome.

That kind of makes you wonder why the United States is not pursuing its development, and if any other countries are?

There are YouTube videos on why we aren’t – mostly stating that the US prefers Uranium because it reacts quicker, and is converted to weapons easier:

http://www.ted.com/talks/kirk_sorensen_thorium_an_alternative_nuclear_fuel

And there are articles on other countries that have started to pick up their research:

http://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/Energy-Voices/2014/0328/Thorium-a-safer-nuclear-power

And even Bill Gates?

http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/bill-gates-is-beginning-to-dream-the-thorium-dream

I’m certainly curious because I’m not sold on the idea of “safe” uranium. For me, Uranium is the very essence of the “opti-grab” – it comes issues that become obvious quickly. And… I know we will need more ENERGY – because eight billion Humans beings will soon be clamoring for it. Then ten billion, then…

Note: My brother makes a case for solar being the first controlled energy, and he notes the south facing living quarters at Mesa Verde. I agree, Mesa Verde is less than 2,000 years old, so it’s pretty recent, but I do feel sure that many early Humans, given the choice of a south-facing cave versus a north-facing one, probably would have understood the differences. The only distinction I might make is about how much “control” they really had – they certainly would have had an awareness. Also, wind and water are currently being harnessed more efficiently than ever before – those technologies will help alleviate some of the energy demands of the inevitable higher populations, but they are limited by the landscape, and location. In Denver we can use wind, but we are lacking in large moving bodies of water. How many windmills would it take to provide all of Denver’s energy needs? I don’t know, but I think it would be TOO many. I’m in the Thorium camp.

Another great blog, thanks. Joe

LikeLike